Multiple Choice

Identify the

choice that best completes the statement or answers the question.

|

|

|

Political Machines Run the

Cities

In the late 19th

century, cities were in trouble. Rapid growth, inefficient government, and a climate of Social

Darwinism opened the way for a power structure, the political machine, and a new politician, the city

boss.

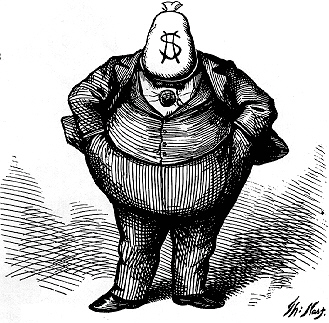

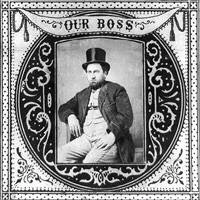

Boss Tweed

THE POLITICAL MACHINE

A political machine was an organized group that

controlled the activities of a political party in a city and offered services to voters and

businesses in exchange for political or financial support. In the decades after the Civil War,

political machines seized control of local government in major cities such as Baltimore, New York,

Philadelphia, Boston, and San Francisco.

The political machine was organized like a pyramid.

At the pyramid's base were local precinct workers and captains, who worked to gain voters'

support on a city block or in a neighborhood and who reported to a ward boss. At election time, the

ward boss worked to secure the vote in all the precincts in the ward, or electoral district. In

return for their votes, people received city jobs, contracts, or political appointments. Ward bosses

helped the poor and gained their votes by doing favors or providing services. As Martin Lomasney,

elected ward boss of Boston's West End in 1885, explained, "There's got to be in every

ward a guy that any bloke can go to ... and get help-not justice and the law, but

help."

At the top of the pyramid was the city boss. The boss controlled the activities of

the political party throughout the city. Like a finely tuned machine, precinct captains, ward bosses,

and the city boss worked together to elect their candidates and guarantee the success of the

machine.

| |

|

|

|

1.

|

The political machine

........

a. | offered services to

voters | d. | received financial

support | b. | offered favors to voters and businesses | e. | all of these are true | c. | received political support

|

|

|

|

2.

|

Political machines

a. | were only active in the Northeast

cities | c. | took control of most major cities in

the U.S. | b. | were active only in hte Midwest cities | d. | had little political power |

|

|

|

3.

|

Political machines were

organized

a. | with democratic and free

elections | c. | from the bottom

up | b. | in a democratic manner with local

committees voting for the people who ran the machine | d. | with the most powerful politician at the top and organized down to the voters

at the bottom. |

|

|

|

4.

|

What opened the way for the

growth of political machines in the big cities in the late 1800’s?

a. | fast growth of the

cities | d. | answers a, b, and c are

correct | b. | government that was not efficient | e. | answers a and b are correct but not c | c. | the idea of Social Darwinism (only the stongest people in

society are meant to survice) |

|

|

|

5.

|

Political machines controlled

the political parties in the big cities after the Civil War.

|

|

|

THE ROLE OF THE POLITICAL BOSS

A city boss controlled thousands of municipal jobs,

including those in the police, fire, and sanitation departments. Whether or not the boss officially

served as mayor, he controlled business licenses and inspections and influenced the courts and other

municipal agencies. Bosses like Roscoe Conkling in New York used their power to build parks, sewer

systems, and waterworks and gave money to schools, hospitals, and orphanages. Bosses could also

provide government support for new businesses, a service for which they were often paid extremely

well.

It was not only money that gave city bosses the drive to deal with urban issues. By

solving problems, bosses could reinforce voters' loyalty, win additional political support, and

extend their influence.

Mr. Schneemann grew up in a city, Philadelphia, controlled by a

Democrat political machine. No one ever paid traffic tickets. If a voter got a ticket, he simply took

it to his local ward boss and the ticket was taken care of. At Christmas the ward boss distributed

food baskets to the poor. If a person wanted a job with the city he did not stand in a line at the

city employment office, He simply went to see his ward boss, who gave him a note to take to city hall

where he was hired. What did the ward boss want in return? At election time everyone in the ward

voted for the Democrat candidates so our political machine could stay in power. Political machines

put a personal face on city government.

| |

|

|

|

6.

|

By controlling city jobs the

political machine enhanced its

a. | image with the

voters | d. | all of

these | b. | political power | e. | none of these | c. | voter loyalty |

|

|

|

7.

|

The political boss and his

machine

a. | was fair to

everyone | d. | none of these are

true | b. | gave supporters preferential treatment | e. | all of these are true | c. | did not

discriminate |

|

|

|

8.

|

At the turn of the century the

cities were filled with immigrants who had many problems. One of the reasons political bosses became

so powerful was because they helped people to solve their problems.

a. | false, the bosses stole from the

immigrants | c. | false, the bosses

only cared about the rich people who lived in the cities | b. | the statement is true | d. | false, the bosses did not really have much

power |

|

|

|

IMMIGRANTS AND THE POLITICAL

MACHINE

Immigrants received sympathetic understanding from

the political machines and in turn became loyal supporters. Many political bosses were

first-generation or second-generation immigrants who had been raised in poverty. Few were educated

beyond grammar school. They entered politics early and worked their way up from the bottom. They

could speak to immigrants in their own language and understood the challenges that newcomers faced.

The bosses not only understood the immigrants' problems but were able to provide solutions. The

machines helped immigrants become naturalized, find places to live, and get jobs-the newcomers'

most pressing needs. In return, the immigrants provided what the political bosses needed

most-votes.

"Big Jim" Pendergast, an Irish-American saloonkeeper, worked his way up

from precinct captain to Democratic city boss in Kansas City by aiding Italian, African-American, and

Irish voters in his ward. By 1900, he controlled Missouri state politics as well, because he

effectively gathered political support.

| |

|

|

|

9.

|

Immigrants

a. | fought against the political

machines | c. | ignored the

political machines | b. | supported political machines | d. | were persecuited by the political

machines |

|

|

|

10.

|

Most political

bosses

a. | were college

educated | c. | started out as

poor immigrants and understood the needs of immigrants | b. | rich upper class

industrialists | d. | did not communicate with immigrants

and only wanted their money |

|

|

|

11.

|

"Big Jim" Pendergast,

was a political boss in

a. | Philadelphia and Kansas

City | c. | Chicago and Kansas

City | b. | Ireland and Kansas City | d. | Kansas City and Missouri |

|

|

|

Municipal Graft and

Scandal

Although the

well-oiled political machines provided city dwellers with vital services, many political bosses fell

victim to greed and corruption as their power and influence grew.

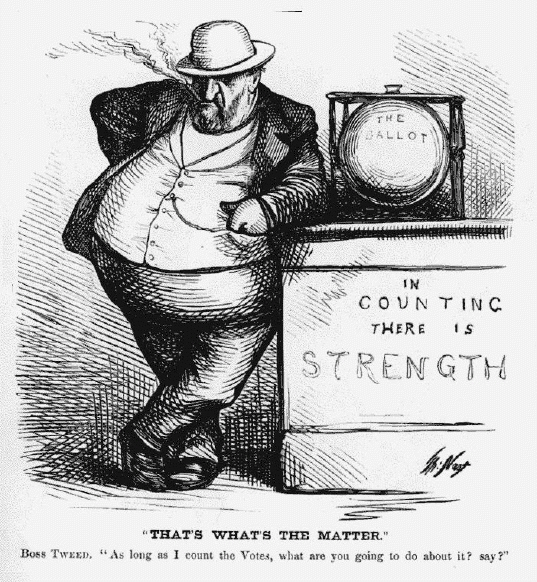

ELECTION

FRAUD AND GRAFT

Since the power of political machines and the loyalty of voters were not

always enough to carry an election, some political machines turned to fraud. They padded the lists of

eligible voters with the names of dogs, children, and people who had died. Then, under those names,

they cast as many votes as were needed to win. In a Philadelphia election, for example, a precinct

with 100 registered voters returned 252 votes.

Once a political machine got its candidates

into office, it could take advantage of numerous opportunities for graft. For example, after hiring a

person to work on a construction project for the city, a political machine could ask the worker to

turn in a bill that was higher than the actual cost of materials and labor. The worker then

"kicked back" a portion of the earnings to the machine. Taking these kickbacks, or illegal

payments, for their services made many political machines-and individual politicians-very

wealthy.

Other ways that political machines made money were by granting favors to businesses

in return for cash and by accepting bribes to allow illegal activities, such as gambling, to

flourish. Politicians were able to get away with shady dealings because the police rarely interfered.

Until about 1890, police forces were hired and fired by political bosses.

| |

|

|

|

12.

|

Political machines

a. | believed in fairness and refused to

fix elections | c. | fixed elections

and did what they needed to do, legal or not, to win | b. | did not tamper with elections because they supported the

idea of democracy | d. | did not base their power on

elections |

|

|

|

13.

|

Political

machines

a. | rigged

elections | d. | helped the people

in their wards | b. | took pay-off from businesses for contracts | e. | all of these are true | c. | used municipal jobs to enhance

power |

|

|

|

14.

|

The political bosses took

kick-backs from workers. A kick-back is

a. | legal in most cities

today | c. | a form of

taxation | b. | a form of graft | d. | a social service |

|

|

|

15.

|

One of the reasons politicians

were able to get away with illegal activities was because

a. | there were no laws against

graft | c. | the politicians did not really

engage in graft | b. | the police were hired and fired by the

politicians | d. | graft is not a form of

stealing |

|

|

|

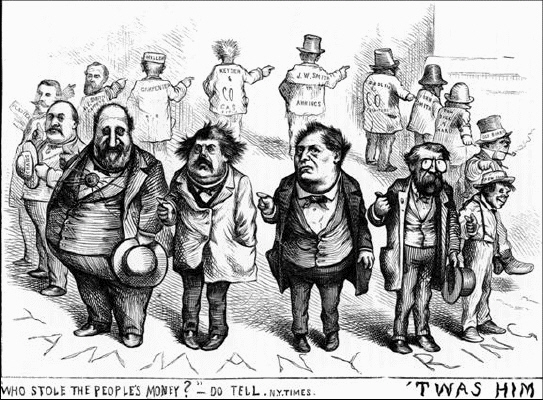

THE TWEED RING SCANDAL

William Marcy Tweed, one of the earliest and most

powerful bosses, became head of Tammany Hall, New York City's powerful Democratic political

machine, in 1868. Between 1869 and 1871, the Tweed Ring, a group of corrupt

politicians led by Boss Tweed, pocketed as much as $200 million from the city in kickbacks and

payoffs. One scheme involving extravagant graft was the construction of the New York County

Courthouse, which cost taxpayers 811 million. The actual construction cost was $3 million; the

rest of the money went into the pockets of Tweed and his followers.

The widespread, profound

graft practiced by Tammany Hall under Boss Tweed's leadership gradually aroused public outrage.

Thomas Nast, a political cartoonist, ridiculed Tweed in the New York Times and in

Harper's Weekly. Nast's work particularly angered Tweed, who reportedly said,

"I don't care what the papers write about me-my constituents can't read; but ... they

can see pictures!"

The Tweed Ring was finally broken in 1871. Tweed was indicted

on 120 counts of fraud and extortion, and in 1873 he was sentenced to 12 years in jail. After

serving two years of his sentence, Tweed escaped. He was later captured in Spain when Spanish

officials identified him from a Thomas Nast cartoon. By that time, corruption had become an issue in

national politics.

| |

|

|

|

16.

|

Boss Tweed

a. | was a political machine

boss | d. | all of these are

true | b. | was governor of New York | e. | none of these are true | c. | a New York church

reformer |

|

|

|

17.

|

Tammany

Hall

a. | was the name for a New York reform

group | c. | was a “gay nineties”

music hall | b. | was a name for the New Youk political

machine | d. | a sports

arena |

|

|

|

18.

|

The Tweed

Ring

a. | was a group of honest business

leaders in New York | c. | was a group of

corrupt political machine leaders led by Boss Tweed | b. | was a group of Republicans loyal to Abraham

Lincoln | d. | Boss Tweed’s poker playing

buddies |

|

|

|

19.

|

In the early 1900s, political

machines tended to exist in urban areas.

|

|

|

20.

|

In the early 1900s, immigrants

tended to oppose political machines.

|

|

|

21.

|

Political machines were

organized like a pyramid, with local precinct captains at the bottom, ward bosses in the middle, and

city bosses at the top.

|

|

|

22.

|

Bribery is any type of

unethical or illegal use of political influence for personal gain.

|

|

|

23.

|

A kickback is a type of illegal

payment.

|

|

|

24.

|

New York’s powerful

political machine, known as the Mafia, was run by William Marcy Tweed and the members of the Tweed

Ring.

|

Matching

|

|

|

a. | Thomas

Nast | e. | kickback | b. | Tweed Ring | f. | Tammany Hall | c. | immigrants | g. | Irish Americans | d. | political machine | h. | graft |

|

|

|

25.

|

illegal payment of a portion

of ones earnings to someone else

|

|

|

26.

|

Group of corrupt politicians

led by Boss Tweed

|

|

|

27.

|

A powerful political machine

in New York

|

|

|

28.

|

A group that controlled a

political party

|

|

|

29.

|

Poloitical Cartoonist who

ridiculed Boss Tweed

|

|

|

30.

|

Illegal use of political

influence for personal gain

|