Multiple Choice

Identify the

choice that best completes the statement or answers the question.

|

|

|

Riding for

Freedom

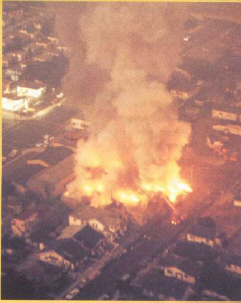

James Peck, a white

civil rights activist, was one of six whites and seven blacks who set out from Washington, D.C ., in

1961 on a special bus ride through the South. The trip was part of CORE’S attempt to test the

Supreme Court decisions banning segregated seating on interstate bus routes and segregated facilities

in bus terminals . The activists formed two interracial teams of freedom riders to travel through the

South challenging |  | segregation . They reasoned that if

they provoked a violent reaction, the Kennedy administration would have to enforce the law. In

Anniston, Alabama, about 200 angry whites attacked Bus Two, kicking its sides and slashing its tires

. The driver managed to take the damaged bus six miles out of town before one of the slashed tires

blew apart. The mob, which had driven after the bus, barricaded the door while someone smashed the

rear window and tossed in a fire bomb . The freedom riders forced open the door and spilled out just

before the bus exploded in a ball of flame.

NEW VOLUNTEERS

CORE’S freedom riders did not want to give up, but

the bus companies refused to carry them any farther, so they ended their ride and nearly all of them

boarded a flight to New Orleans . Then Diane Nash, a SNCC leader, called CORE director James Farmer

to say that a group of Nashville students wanted to resume the freedom ride. “You know that may

be suicide,” warned Fariner. Nash answered, “We know that, but if we let them stop us

with violence, the movement is dead! . . . Your troops have been badly battered. Let us pick up the

baton and run with it When the SNCC volunteers rode into Birmingham, Police Commissioner Eugene

“Bull” Connor’s men pulled them off the bus, beat them, and drove them into

Tennessee. The determined young people returned to Birmingham and occupied the whites-only waiting

room at the terminal, where they sat for 18 hours because the bus driver refused to risk his life

transporting them. After receiving an angry phone call from U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy, bus

company officials convinced the driver to proceed. The SNCC volunteers set out for Montgomery on

May20. | | |

|

|

|

1.

|

Why did groups of civil rights

workers start out on “Freedom Rides” through the South?

a. | It was safer to ride in

groups | c. | They wanted to test the Supreme

Court decision that desegregated interstate buses. | b. | Freedom busses were the only transportation available in

the South | d. | The Freedom Bus Company had the

cheapest fairs in the South |

|

|

|

2.

|

What organization sponsored the

Freedom Rides?

a. | Colored Organizations for Racial

Equality | c. | Congress Of Racial

Equality | b. | Colored Organizers for Racial Equality | d. | Congressional Officers for Ending

Racism |

|

|

|

3.

|

Who was the police commissioner

of Birmingham who tried to break up the Freedom Rides?

a. | Bull

Conners | c. | James

Farmer | b. | George Wallace | d. | James Peck |

|

|

|

4.

|

Which organization was most

aggressive and confrontational about fighting for racial integration

a. | NAACP | c. | SNCC | b. | CORE | d. | None of these were aggressive |

|

|

|

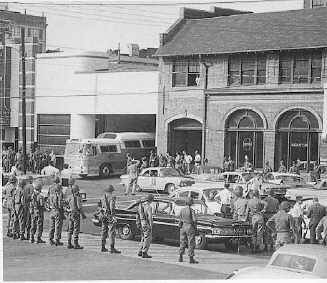

| ARRIVAL OF

FEDERAL MARSHALS

Although Alabama officials had promised Kennedy that the riders would be

protected, no police were stationed near the Montgomery terminal when the bus arrived. Instead, a mob

of whites-many carrying bats and lead pipes-fell upon the riders . John Doar, a Justice Department

official on the scene, called the attorney general and reported what happened. “A bunch of men

led by a guy with a bleeding face are beating [the passengers] . There are no cops.

It’s terrible . It’s terrible . There’s not a cop in sight. People are yelling,

‘Get ‘em, get ‘em.’ It’s awful.” The violence

| provoked exactly the response the freedom riders had been

hoping for. Newspapers throughout the nation and abroad denounced the beatings. Southern

newspapers such as the Atlanta Constitution, which had criticized the freedom ride, expressed outrage

that police had refused to protect the riders . President John F Kennedy decided to give the

freedom riders more direct support. This time, the justice Department sent 400 U.S . marshals to

protect the riders on the last part of their journey to Jackson, Mississippi. In addition, the

attorney general and the Interstate Commerce Commission issued an order banning segregation in all

interstate travel facilities, including waiting rooms, restrooms, and lunch counters

.

| | |

|

|

|

5.

|

What happened when the Freedom

Riders arrived in Montgomery, Alabama?

a. | They were beaten by the

police | c. | They were greeted by the

mayor | b. | They were beaten by an angry mob | d. | They were met by angry Justice Department

officials |

|

|

|

6.

|

What was the attitude of the

police toward the violence imposed on the Freedom Riders when they arrived in

Montgomery?

a. | They condoned

it | c. | They instigated

it | b. | They opposed

it | d. | They most likely did not know about

it |

|

|

|

7.

|

How did the Justice Department

react to the beatings of the Freedom Riders in Montgomery?

a. | They ignored the

beatings | c. | They sent federal

marshals to protect the riders | b. | They condoned the beatings | d. | They took control of the bus

company |

|

|

|

8.

|

Interstate commerce means commerce between two or more states, not just inside a state.

The U.S. government has authority over interstate commerce because it is between states. What was the

result of the Freedom Rider beatings in Montgomery?

a. | The Freedom Riders gave

up. | c. | The bus company stopped freedom

rides because they involved interstate commerce. | b. | segregation was banned on all travel facilities, including

waiting rooms, restrooms, and lunch counters by the state of

Alabama | d. | segregation was banned on all travel facilities, including

waiting rooms, restrooms, and lunch counters by the U.S.

government |

|

|

|

9.

|

What was the end result of the

Freedom Rider beatings in Montgomery, Alabama?

a. | public opinion turned in against the

Riders and segregation was banned on the busses | c. | public opinion turned in favor of the Riders and segregation was banned on the

busses. | b. | public opinion turned in favor of the police and gave them more power to

impose law and order in Montgomery | d. | the State of Georgia and the city of Montgomery came out looking like the

victims |

|

|

|

10.

|

The Interstate Commerce

Commission is an agency of

a. | the state of

Alabama | c. | the Constitution

of the United States | b. | the city of Birmingham, Alabama | d. | the United States government |

|

|

|

Standing Firm

As interstate travel

facilities became more fully integrated, some civil rights workers turned their attention to

integrating some Southern schools and pushing the movement into additional Southern towns. At each

turn they encountered opposition from some whites .

“Violence is a fearful thing,”

recalled Avon Rollins of SNCC . “I remember when I had to take a stand, where the words

wouldn’t come out of my mouth, . . . because the fear was in me so strong

.”

INTEGRATING OLE MISS

In September 1962, Air Force veteran James Meredith won a

federal court case that allowed him to enroll in the all-white University of Mississippi, nicknamed

Ole Miss. But when Meredith arrived on campus, he faced Governor Ross Barnett, who refused to let him

register as a student. Following the precedent set by Eisenhower in Little Rock, President

Kennedy ordered federal marshals to escort Meredith to the registrar’s office . Barnett

responded with a heated radio appeal : “I call on every Mississippian to keep his faith and

courage. We will never surrender.” The broadcast turned out white demonstrators by the

thousands . On the night of September 30, riots broke out on campus that resulted in two deaths . It

took more than 5,000 soldiers, 200 arrests, and 15 hours to stop the rioters . In the months that

followed, federal officials accompanied Meredith to class and protected his parents from nightriders

who shot up their house.

| |

|

|

|

11.

|

When _____ arrived on the

University of Mississippi to enroll, he was opposed by _____ .

a. | James Meredith - Governor Ross Barnett | c. | Freedom Riders - the Justice Department | b. | James Meredith - Governor George

Wallace | d. | Avon Rollins - Governor Ross

Barnett |

|

|

|

12.

|

What did the U.S. government do

in regards to the enrollment of James Meredith at “Ole Miss”

a. | Correctly stated that it was a state

matter and the U.S. government had no authority | c. | Sent marshals to protect and escort Meredith to

class | b. | Asked former President, Eisenhower to

intervene. | d. | Cut off all federal funds to the

University of Mississippi |

|

|

|

13.

|

How did the people of

Mississippi react to the radio speech of the Governor?

a. | By rioting on campus

| c. | The people ignored

it | b. | They calmed

down | d. | By dropping out of the

University |

|

|

|

HEADING INTO BIRMINGHAM By 1963, Reverend

Fred Shuttlesworth, head of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, decided that something

had to be done about Birmingham-a city known for its strict enforcement of total segregation in

public life . The city also had a reputation for racial violence, including 18 bombings from 1957 to

1963. Deciding that Birmingham would be the ideal place to test the power of nonviolence,

Shuttlesworth invited Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and the SCLC to help desegregate the city. On

April 3, 1963, King flew into Birmingham to hold planning meetings with members of the

African-American community. “This is the most segregated city in America,” he said.

‘We have to stick together if we ever want to change its

ways.”

After several days

of demonstrations led by Shuttlesworth and others, King led a small band of marchers into the streets

of Birmingham on Good Friday, April 12. Police Commissioner Bull Connor promptly arrested them. While

sitting in his jail cell, Dr. King wrote an open letter to white religious leaders who felt he was

pushing too hard, too fast .

On April 20, King posted bail and began to plan more demonstrations .

On May 2, more than a thousand African-American children marched in Birmingham ; Bull Connor arrested

959 of them. On May3, a second “children’s crusade” came face to face with Connor

and his helmeted police force . As television cameras recorded the scene, the police swept the

marchers off their feet with high-pressure fire hoses, set attack dogs on them, and clubbed those who

fell . Millions of TV viewers heard the children screaming. Continued protests, an economic

boycott, and negative media coverage finally convinced Birmingham officials to meet King’s

demands for an end to segregation . Birmingham offered a stunning civil rights victory that inspired

African Americans across the nation. In addition, it convinced President Kennedy that nothing short

of a new civil rights act would end the disorder and satisfy the demands of African Americans-and

many whites-for racial justice.

|

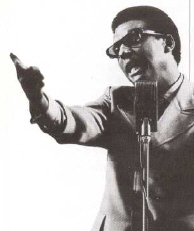

Dr King speaks in

Birmingham

Police dogs attack

demonstrators

Bull Conners - Police Chief of Birmingham,

Alabama | | |

|

|

|

14.

|

Birmingham, Alabama was chosen

as a city to test the non-violent approach to ending segregation because

a. | it had a history of

violence | c. | both of these

reasons | b. | it was one of the most segregated cities in the

nation |

|

|

|

15.

|

It is safe to say that Dr. King

and the _____ was trying to _____ violence to call attention to the segregation

issue.

a. | SNCC -

provoke | c. | SCLC - avoid

| b. | SCLC - provoke

| d. | SNCC -

prevent |

|

|

|

16.

|

Which person did exactly what

his opposition wanted him to do in Birmingham.

a. | Dr.

King | c. | President John

Kennedy | b. | Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth | d. | Bull Conners |

|

|

|

17.

|

What was the result of Bull

Conners actions in Birmingham?

a. | Thousands of demonstrators were

killed | c. | The city was

desegregated | b. | The city became more segregated | d. | Most of the black children in the city were beaten and

jailed. |

|

|

|

18.

|

The events in Birmingham,

Alabama in 1963 demonstrated

a. | the fact that the American people

did not care what happened to African Americans | c. | the basic fairness of the American people when exposed to an

injustice | b. | the indifference of the Kennedy administration toward racial

injustice | d. | that the American people did not

want to integrate with African Americans |

|

|

|

George Wallace

Medgar Evers

JFK

| KENNEDY TAKES A STAND

On June 11, 1963, President Kennedy used federal troops to

force Governor George Wallace to honor a court order desegregating the University of Alabama. That

evening, Kennedy addressed the nation and asked pointedly, “Are we to say to the world-and much

more importantly, to each other-that this is the land of the free, except for the Negroes?” He

referred directly to “repressive police action” and “demonstrations in the streets

.” Then, he demanded that Congress pass a sweeping civil rights bill A tragic event just hours

after Kennedy’s speech highlighted the racial tension in much of the South. Shortly after

midnight, a sniper shot and killed Medgar Evers-NAACP field secretary and World War II veteran-in the

driveway of his home in Jackson, Mississippi. Police soon arrested white supremacist Byron de la

Beckwith for the crime, but he was released after two trials resulted in hung juries . (De la

Beckwith was finally convicted in 1994, after the case was reopened based on new evidence .) The

release of de la Beckwith brought a new militancy to African Americans. With raised fists, many

demanded, “Freedom now!”

Byron de la

Beckwith Medgar

Evers

| | |

|

|

|

19.

|

Medgar Evers was

a. | a WWII veteran and NAACP field

worker | c. | Governor of

Alabama | b. | President of the U.S. | d. | charged with murder |

|

|

|

20.

|

JFK was

a. | a WWII veteran and NAACP field

worker | c. | charged with

murder | b. | President of the U.S. | d. | Governor of Alabama |

|

|

|

21.

|

Beckwith

was

a. | Governor of

Alabama | c. | charged with

murder | b. | President of the U.S. | d. | a NAACP field worker |

|

|

|

22.

|

George Wallace

was

a. | charged with

murder | c. | an NAACP field

worker | b. | Governor of Alabama | d. | leader of SNNC |

|

|

|

23.

|

What did Kennedy ask Congress

to do?

a. | pass a civil rights

bill | c. | send marshals to Alabama to enforce

segregation | b. | send troops to Alabama to protect

demonstrators | d. | send marshals to Alabama to enforce

integration |

|

|

|

24.

|

Byron de la Beckwith was

arrested and convicted in 1963 for shooting Medgar Evers

|

|

|

25.

|

How did African Americans react

to the trial of de la Beckwith in 1963?

a. | satisfaction | c. | anger | b. | sadness | d. | anticipation |

|

|

|

| Marching to Washington

The civil rights bill

that Kennedy sent to Congress guaranteed equal access to all public accommodations and gave the U.S.

attorney general the power to file school desegregation suits. To persuade Congress to pass the bill,

two veteran organizers-labor leader A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Bustin of the SCLC summoned

Americans to join in a massive march on Washington, D.C.

THE DREAM OF EQUALITY

On August

28, 1963, more than 250,000 people including about 75,000 whites-converged on the nation’s

capital. They assembled on the grassy slopes of the Washington Monument, and the movement’s

leaders, walking arm in arm, led the crowd to the sprawling plaza near the Lincoln Monument. There,

for more than three hours, people listened to speakers demand the immediate passage of the civil

rights bill. When Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., appeared, the crowd exploded in applause . King

eventually stopped reading from his prepared text and began an improvised speech in which he appealed

for peace and racial harmony, punctuating his speech with the repeated refrain “I have a

dream.”

MORE VIOLENCE

Two weeks after King’s historic speech, a car sped past

the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, and a rider in the car hurled a bomb

through one of the church “windows. The resulting explosion claimed the lives of four

young girls .

Two more African Americans died in the unrest that followed. Two months

later, on November 22, 1963, an assassin shot and killed John F. Kennedy. (See Chapter 20.) His

successor, President London B. Johnson, pledged to carry on Kennedy’s work by winning passage

of the civil rights bill. “We have talked for 100 years or more,” Johnson said. “It

is time now to write the new chapter-and to write it in books of law.” On July 2, 1964,

President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited discrimination because of

race, religion, national origin, and gender. It gave all citizens the right to enter libraries,

parks, washrooms, restaurants, theaters, and other public accommodations

.

| |

|

|

|

26.

|

The civil rights bill that

Kennedy sent to Congress

a. | guaranteed equal access to all

public accommodations | c. | gave the U.S.

attorney general the power to file school desegregation suits | b. | both of these | d. | Neither of these. Kennedy was luke- warm on civil

rights |

|

|

|

27.

|

Why did A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Bustin of the SCLC organize the “March on

Washington?”

a. | demand better housing for black

people | c. | pressure Congress to pass the civil

rights bill | b. | demand and end to school integration | d. | protest the war in Vietnam |

|

|

|

28.

|

Dr. King’s “I Have

A Dream” speech

a. | was carefully prepared to get just

the right response from the abundance | c. | was a spontaneous speech from his heart | b. | was written by Bayard Bustin and A. Philip

Randolph | d. | surprised people because it was full

of anger, frustration and some hate. |

|

|

|

29.

|

The March on Washington seemed

to have a calming effect on the citizens of Birmingham, Alabama

|

|

|

30.

|

When was John F.Kennedy

assassinated?

a. | Nov. 22,

1964 | c. | January,

1963 | b. | Nov 22, 1963 | d. | January, 1964 |

|

|

|

31.

|

What happened to the civil

rights bill after Kennedy was assassinated?

a. | It died in

Congress | c. | Johnson pushed it

through Congress | b. | It was defeated in the Senate | d. | Johnson let it die and did not push

it |

|

|

|

32.

|

What happened on July 2,

1964?

a. | President Johnson signed the Civil

Rights Bill | c. | President Kennedy

was shot | b. | President Kennedy signed the Civil Rights

Bill | d. | President Johnson forgot to sign the Civil Rights Bill

because he was working out with Mr. Schneemann |

|

|

|

Fighting for Voting

Rights

Meanwhile, civil rights

workers in the South were planning a different campaign to influence the country’s laws-by

registering African-American voters who could elect legislators who supported civil rights .

Because previous voter-registration drives had met with little success, CORE and SNCC planned a much

larger effort for 1964. They hoped their campaign would receive national publicity that would in turn

influence Congress to pass a voting rights act. SNCC concentrated its efforts in Mississippi, in a

project that was popularly known as Freedom Summer.

FREEDOM SUMMER

SNCC knew that challenging the system that kept more than 90 percent of

African-American citizens from the polls would be a daunting task. Civil rights groups recruited

white students from colleges across the country and then trained them in the techniques of nonviolent

resistance . Some 1,000 volunteers-mostly white, about one-third finally-went into Mississippi to

help the mostly African-American SNCC staff members register voters .

Robert Moses, a former New

York City schoolteacher who had quit his job and joined SNCC in 1961, led the voter project in

Mississippi. By the summer of 1964, Moses had already been working for several years in Mississippi

to register blacks to vote. “Mississippi has been called ‘The Closed Society.’ It

is closed, locked,” Moses said. “We think the key is in the

vote.”

Immediately, the voter

project encountered violent opposition . In June, while some of the volunteers were still receiving

training back in Ohio, three civil rights workers, including one summer volunteer, disappeared in

Mississippi . They were Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman, white activists from New York, and

James Chaney, an African American from Mississippi . Investigators later learned that Klansmen, with

the support of local police, had murdered the three and buried them in an earthen dam . By the end of

the summer, the project had suffered 4 dead, 4 critically wounded, 80 beaten, and dozens of

African-American churches and businesses bombed or burned. In spite of all the publicity the project

received, Congress still did not pass a voting rights act

| |

|

|

|

33.

|

What was CORE and SNCC trying

to do in Mississippi during the Summer of 64?

a. | Get black people registered to

vote | c. | Fight Bull Conners in

Birmingham | b. | Protest against discrimination in interstate

commerce. | d. | Protect black people from the KKK in

the South. |

|

|

|

34.

|

What did CORE and SNCC want the

U.S. government to do

a. | protect the protestors on

busses | c. | pass an anti poverty

bill | b. | pass a voting rights act | d. | go after the KKK |

|

|

|

35.

|

Many people thought that

Mississippi was a closed society to black people. They could not improve their living conditions and

could not even acquire basic civil rights. What did the civil rights organizers see as the key to

open the state for black people.

a. | better

jobs | c. | total integration of the

schools | b. | a stronger NAACP | d. | voting rights for black people |

|

|

|

36.

|

Freedom Summer was the first

Summer in years free of violence against civil rights workers.

|

|

|

37.

|

Because of the hard work and

dedication of the civil rights workers during Freedom Summer, the Voting Rights Act was finally

passed in the fall.

|

|

|

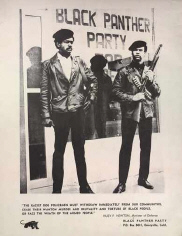

A NEW POLITICAL PARTY

The Democrat party had controlled

the South since the Civil War. They were in favor of segregation and created the Jim Crow laws. To be

elected to political office in the South you had to be a Democrat. To challenge Mississippi’s

white-controlled Democratic Party, SNCC organized the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) .

Open to anyone, regardless of race, the MFDP hoped to unseat Mississippi’s regular party

delegates at the Democratic National Convention .

Fannie Lou Homer, the daughter of Mississippi

sharecroppers, won the honor of speaking for the MFDP at the convention . Hamer had registered to

vote in 1962 at the cost of a crippling beating and her family’s eviction from their faun. In

June 1964, she spoke to the credentials committee at the Democratic convention in a prime-time

televised address . Hamer described how she had been arrested for trying to register and taken to

jail, where police forced other prisoners to beat her.

In response to Hamer’s speech, telegrams and

telephone calls poured in the convention in support of seating the MFDP delegates . But President

Johnson feared that such a move would cost him white votes throughout the South, so his

administration pressured civil rights leaders to convince the MFDP to accept a compromise. The

Democrats would give 2 of Mississippi’s 68 seats to the MFDP, with a promise to ban

discrimination at the 1968 convention. When Hamer learned of the compromise, she exclaimed, “We

didn’t come all this way for no two seats when all of us is tired.” The MFDP and many of

their young supporters in SNCC felt that the leaders of other civil rights groups had betrayed them.

This sense of betrayal was one of several factors that eventually led to conflict among various civil

rights groups

| |

|

|

|

38.

|

What was the goal of the

Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP)?

a. | gain power in the regular Democrat

party | d. | all of

these | b. | get some seats for black people in the Democrat convention in

1964 | e. | none of these | c. | gain political power in

Mississippi |

|

|

|

39.

|

SNCC and MFDP

believed

a. | they were betrayed at the Democrat

National Convention | c. | they were now the

most important and powerful political force in Mississippi | b. | they had won a victory at the Democrat Convention

| d. | the regular Democrat party was a friend of black

people |

|

|

|

40.

|

Why did SNCC believe it needed

its own political party in Mississippi?

a. | the regular Democrats in Mississippi

were controlled by people who were friendly to civil rights but they had little real political

power | c. | the regular Democrat party in

Mississippi was against racial integration and at the same time controlled the

state | b. | the Republicans controlled the South and it was the only way to defeat

them | d. | they could not raise money without the organization of

regular political party |

|

|

|

THE SELMA CAMPAIGN

Voting in the

United States is a two step process. First you must register with the country to prove you are a

citizen and then you can vote on election day. In the South black people usually did not register so

they could not vote. They did not register for a variety of reasons: some states had literacy

requirements which said you needed to be able to read and write, sometimes blacks felt intimidated,

sometimes they had to pay a poll tax to register, sometimes they were not motivated because the only

candidates were pro segregationists.

At the start of 1965, the SCLC decided to conduct a

major campaign in Selma, Alabama, where SNCC had been working for two years to register voters .

African Americans accounted for more than half of Selma’s population but for only about 3

percent of the total registered voters . Martin Luther King, Jr., and the SCLC hoped that a

concentrated voter-registration drive in Selma would provoke a hostile white response-which would

help convince the Johnson administration of the need to sponsor a federal voting-rights law.

By the end of January 1965, more than 2,000 African Americans had been arrested in

demonstrations . Selma sheriff Jim Clark reacted as violently as Bull Connor in Birmingham, and his

men brutally attacked civil rights demonstrators Then, in February, law officers shot and killed a

demonstrator named Jimmie Lee Jackson. Dr.King responded by announcing a 50-mile protest march from

Selma to the state capital, Montgomery. On Sunday, March 7, 1965, a group of about 600 protesters set

out for Montgomery.That night, news bulletins interrupted regular television programs to show what

looked like a war. Clouds of tear gas swirled around fallen marchers, while police wearing gas masks

and riding horses swung whips and clubs. The scene sent shock waves across the country. Demonstrators

from all over the United States poured into Selma to join the march. President Johnson responded by

asking Congress for the swift passage of a new voting rights act. In his speech, Johnson openly

embraced the rhetoric of the civil rights movement. Said the president, “Their cause must be

our cause, too. It is not just Negroes, but all of us, Who must overcome the crippling legacy of

bigotry and injustice . And we shall overcome .” On Sunday, March 21, 3,000 marchers again set

out for Montgomery~; this time with federal protection. Two Nobel Peace Prize winners-Dr. Martin

Luther King, Jr., and UN diplomat Ralph Bunche-led the procession . Under court order, only 250

marchers were supposed to enter the city limits, but nothing could stop the groundswell of support.

An army of some 25,000 demonstrators joined the marchers as they walked into

Montgomery

| |

|

|

|

41.

|

Why did Dr. King try to provoke

violence against the civil rights workers and marchers?

a. | Gain the sympathy of the General

Public | c. | Motivate his

workers | b. | Frighten President Johnson into supporting a new voting rights

law | d. | All of these are

reasons |

|

|

|

42.

|

Before you can vote in the

United States you must

a. | pay all traffic tickets and

fines | c. | have a high school

education | b. | register | d. | prove you could read and write |

|

|

|

43.

|

In what southern city did SCLC

and SNCC focus their attention because only about 3% of the voters were African American while their

percentage of the total population was more than half.

a. | Montgomery,

Alabama | c. | Selma,

Alabama | b. | Little Rock, Arkansas | d. | Selma, Mississippi |

|

|

|

44.

|

The march to Selma started with

about 600 marchers. How did sheriff Jim Clark react to the

marchers?

a. | violently with tear gas and

clubs | c. | called out the National

Guard | b. | He protected the marchers from the mobs of people who came to break up the

march | d. | resigned rather than follow the mayor’s orders to

break up the march |

|

|

|

45.

|

The reaction of sheriff Jim

Clark to the Selma civil rights marchers

a. | horrified the leaders of SNCC and

SCLC | c. | was just the response that Dr. King,

SNCC and SCLC wanted | b. | angered Dr. King | d. | did not get shown to the rest of the country on

television |

|

|

|

46.

|

Who was the black United

Nations diplomat from the U.S. who marched with Dr. King in Selma?

a. | Dr. Bull

Conners | c. | Dr. Ralph

Bunche | b. | Dr. Ralph Clark | d. | Dr. Jim Crow |

|

|

|

VOTING RIGHTS ACT OF 1965

Ten weeks after the

Selma-to-Montgomery march, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 . The act eliminated the

literacy test that had disqualified so many voters . The act also stated that federal examiners could

enroll voters denied suffrage by local officials. In Selma, the proportion of eligible African

Americans who were registered to vote rose from 10 percent in 1964 to 60 percent in 1968. Overall the

percentage of registered African-American voters in the South tripled. Although the Voting

Rights Act marked a major civil rights victory, some African Americans felt that the law did not go

far enough. Centuries of segregation and discrimination had produced deep-rooted social and economic

inequalities. In the mid-1960s, anger over these inequalities led to a series of violent disturbances

in the cities of the North. | |

|

|

|

47.

|

The Voting Rights Act on 1965

said that the U.S. government could register voters if they were denied voting rights by local

communities and also said that a person did not have to know how to read and write to register to

vote.

a. | true | c. | partly true and partly

false | b. | false |

|

|

|

48.

|

The Voting Rights Act of 1965

_____ the number of African American voters eligible to vote.

a. | decreased to

60% | c. | increased to

60% | b. | increased to 100% | d. | did not effect |

|

|

|

49.

|

Black people were satisfied

that they had full political power now that they had the Voting Rights Act of

1965

|

|

|

50.

|

What does suffrage

mean?

a. | The right to protest and not have to

suffer | c. | The persecution of African Americans

in the South | b. | The right to march and not have to suffer | d. | The right to vote |

|

|

|

The Segregation

System

Segregated buses might

never have rolled through the streets of Montgomery or anywhere else in the United States-if the

Civil Rights Act of 1875 had remained in force. This act outlawed segregation in public facilities by

decreeing that “all persons . . . shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of the

accommodations . . . of inns, public conveyances on land or water, theaters, and other places of

public amusement.” In 1883, however, the Supreme Court declared the act

unconstitutional

| | PLESSY V. FERGUSON

During the 1890s, a number of other court decisions and

state laws severely limited African-American rights . In 1890, Louisiana passed a law requiring

railroads to provide “equal but separate accommodations for the white and colored races.”

In the Plessy v. Ferguson case in 1896, the Supreme Court ruled that this law did not violate the

Fourteenth Amendment, which guarantees all Americans equal treatment under the

law.

Armed with the Plessy

decision, states throughout the nation, but especially in the South, passed what were known as Jim

Crow laws, or laws aimed at separating the races. Laws forbade marriage between blacks and whites and

established many other restrictions on social and religious contact between the races . There were

separate schools, as well as separate streetcars, waiting rooms, railroad coaches, elevators, witness

stands, and public restrooms. The facilities provided for blacks were always far inferior to those

provided for whites . Nearly every day, African Americans faced humiliating signs that read, Colored

Water; No Blacks Allowed; Whites Only. | | |

|

|

|

51.

|

In 1873 a civil rights act was

passed that made segregation unconstitutional in the United States. If this is true, why did

segregation continue until the late 1900’s?

a. | The government refused to enforce

the law | c. | People in the

North ignored the law | b. | The Supreme Court said the law was

unconstitutional | d. | People in the South ignored the

law |

|

|

|

52.

|

The 14th Amendment to the U.S.

Constitution says that the law must be applied equally to all citizens. In the Plessy v. Ferguson case in 1896, what did the Supreme Court rule?

a. | The U.S. government should not

interfere in segregation cases. | c. | Separate facilities for the races did not violate the 14th

Amendment | b. | Slavery is unconstitutional | d. | Separate facilities for the races did violate the 14th

Amendment |

|

|

|

53.

|

What were Jim Crow

laws?

a. | Laws designed to separate the

races | c. | Law that forbid the sale of bourbon

whisky to African Americans | b. | Laws designed to bring the races together | d. | Laws designed to protect black

people |

|

|

|

SEGREGATION

CONTINUES INTO THE 20TH

CENTURY

In the late 1800s, some

African Americans tried to escape Southern racism by moving north. This migration of Southern African

Americans speeded up greatly during World War I, as many African-American sharecroppers abandoned the

farms for the promise of industrial jobs in Northern cities . However, once African Americans reached

the North, they discovered that racial prejudice and segregation patterns existed there as well. Most

African Americans could find housing only in all black neighborhoods. In addition, many white workers

resented competition from blacks, resentment which sometimes led to violence . |

African American war

plant workers | | In many ways, the events of World War II

set the stage for the civil rights movement. First, the demand for soldiers in the early 1940s

created a shortage of white male laborers, which opened up new job opportunities for African

Americans, Latinos, and white women. Second, about 700,000 African Americans served in the

armed forces, which needed so many fighting men that they gradually had to end discriminatory

policies that had kept African Americans from serving in fighting units. Many African-American

soldiers returned from the war determined to fight for their own freedom now that they had helped

defeat Fascist regimes overseas . Third, during the war, civil rights organizations actively

campaigned for African-American voting rights and challenged Jim Crow laws. In response to protests,

President Roosevelt issued a presidential directive prohibiting racial discrimination by federal

agencies and all companies that were engaged in war work. The groundwork was laid for more organized

campaigns to end segregation throughout the United States. | | |

|

|

|

54.

|

During the 20th century many

African Americans moved from the South to the North. What was the main motivation for this

migration?

a. | The civil rights movement was

stronger in the North | c. | In the North there

was no segregation | b. | Good paying factory jobs in the North | d. | Martin Luther King encouraged blacks to move

North |

|

|

|

55.

|

Which World War II events

motivated black people to want more civil rights and set the stage for the civil rights

movement of the 50’s and 60’s?

a. | Black men serving in the

military | d. | Roosevelt

declaring an end to segregation in war industries | b. | Blacks working in the war

plants | e. | All of these set the state for the civil rights

movement | c. | Civil rights leaders campaigned for an end to Jim Crow laws and for voting

rights |

|

|

|

56.

|

In World War II African

Americans

a. | secretly wanted Japan to win the war

because they were not white | c. | were pro American patriots who worked and fought for the United

States | b. | agreed with the Black Muslims who refused to help the U.S. in the

war | d. | hated the United States because of

segregation |

|

|

|

Challenging

Segregation in Court

Since 1909, the NAACP had fought to end segregation. One influential

figure in this campaign was Charles Hamilton Houston, a brilliant Howard University professor who

trained African-American law students and who also served as chief legal counsel for the NAACP from

1934 to 1938.

|

Thurgood

Marshall | THE NAACP LEGAL STRATEGY - In

deciding the NAACP’s legal strategy, Houston considered the blatant inequality between the

separate schools many states provided for the two races . At that time, the nation spent ten times as

much money educating a white child as it did educating an African-American child. It was to redress

this injustice that Houston chose to focus the organization’s limited resources on challenging

segregated public education .

For help, Houston recruited some of his most able law students

to prepare a battery of cases to take before the Supreme Court. In 1938, he placed the team under the

direction of Thurgood Marshall. Over the next 23 years, Marshall and his NAACP lawyers would win 29

out of 32 cases argued before the Supreme Court. Several of the cases that Marshall and his team of

lawyers won became legal milestones, each one chipping away at the segregationist tenets of Plessy v.

Ferguson .

· In the 1946 case

Morgan v. Virginia, the Supreme Court declared unconstitutional those state laws mandating

segregated seating on interstate buses .

· In 1950, the high court

ruled in Sweatt v. Painter that state law schools must admit black applicants, even if

separate black schools exist.

·

In another 1950 case that Marshall and his team argued, the court ruled

that blacks admitted to state graduate schools were entitled to the use of all the school’s

facilities.

· BROWN V. BOARD OF EDUCATION Marshall’s most stunning victory came on May

17, 1954, in the case known as Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas . In this case, the

court responded to a brilliant legal brief written by Marshall that addressed segregated education in

four states-Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, and Delaware. The court lumped the state cases together

in a single ruling named for the case concerning nine-year-old Linda Brown. Her father, Oliver Brown,

had charged the board of education of Topeka with violating Linda’s rights by denying her

admission to an all-white elementary school four blocks from her house. The state had directed Linda

to cross a railroad yard and then take a bus to an all-black elementary school 21 blocks away.

In a landmark verdict, the Supreme Court unanimously struck down segregation as unconstitutional .

The Court’s decision, written by Chief Justice Earl Warren, in part stated the

following.

To

separate [African-American children] from others of similar age and qualifications solely

because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may

affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone. . . . We conclude that in the

field of public education the doctrine of “separate but equal” has no place. Separate

educational facilities are inherently unequal .

CHIEF JUSTICE EARL WARREN, Brown v. Board of

Education

| | |

|

|

|

57.

|

How did Charles Hamilton Houston decide to attack racism?

a. | In the

streets | c. | In the

courts | b. | In the workplace | d. | In the inner city |

|

|

|

58.

|

Charles Hamilton Houston was

especially upset of inequality in

a. | the work

place | c. | in the

churches | b. | in the schools | d. | in the military |

|

|

|

59.

|

What was the 1946 case Morgan v. Virginia case concerned with?

a. | segregation in the

workplace | c. | segregation in

transportation | b. | segregation in the military | d. | segregation in schools |

|

|

|

60.

|

What was the Sweatt v. Painter case about

a. | admission of black applicants to law

schools | c. | work place

segregation | b. | promotion of blacks in the military | d. | admission of black men to medical

colleges |

|

|

|

61.

|

What was the name of the very

able African American lawyer who worked with the NAACP for 23 years and won 29 of the 32

cases he argued before the Supreme Court?

a. | Plessy

Fergusson | c. | Charles

Hampton | b. | Charles Houston | d. | Thurgood Marshall |

|

|

|

62.

|

What was the Brown v Board of

Education case all about?

a. | A nine year old girl, Linda Brown,

was not allowed to go to a white school 4 blocks from her house because she was

black | c. | Linda Brown was not permitted to go

to an all black school, just 4 blocks from her house. | b. | Linda Brown, a white girl, was forced to go to an all

black school as part of a forced integration plan for Topeka,

Kansas | d. | Linda Brown could not go to school because there were not

black schools in Topeka, Kansas |

|

|

|

63.

|

There are 9 judges on the

Supreme Court. How many voted to end segregation in the Brown v Board of Education

case.

|

|

|

64.

|

Earl Warren was a conservative

Republican appointed to the Supreme Court by Republican President, Dwight Eisenhower. How did Warren

feel about segregation in public schools?

a. | He was in favor of segregation as

long as the schools for blacks and whites were equal | c. | He was opposed to segregated schools because black and white school were

inherently unequal | b. | He was not if favor of segregated schools, even though he thought black and

white schools could be equal | d. | He had no opinion about segregated

schools and thought the U.S. government should stay out of the

controversy. |

|

|

|

65.

|

The Brown v Board of Education

decision was based on the 14th Amendment to the Constitution of the U.S. What constitutional

principle is part of the 14th Amendment.

a. | free

speech | c. | equal protection of the

law | b. | freedom of the press | d. | the right to have a lawyer in

court |

|

|

|

Reaction to the Brown

Decision

The ruling thrilled

African Americans and many other Americans . “I was so happy, I was numb,” declared

Thurgood Marshall . The Chicago Defender, an African-American newspaper, pronounced,

“[It’s] a second emancipation proclamation .” The Brown decision

immediately affected some 12 million school children in 21 states . Official reaction to the ruling

was mixed. In Kansas and Oklahoma, state officials said they expected segregation to end with little

trouble. In Texas the governor promised to comply but warned that plans might “take

years” to work out. In Mississippi and Georgia, officials vowed total resistance. Governor

Herman Talmadge of Georgia branded the decision “a flagrant abuse of judicial power” and

pledged, “The people of Georgia . . . will map a program to insure . . . permanent segregation

of the races .” | |

|

|

|

66.

|

How did the states react to the

Brown v Board of Education decision?

a. | The reaction was solidly against the

decision | c. | The reaction was

mixed | b. | The reaction was solidly for the decision | d. | The states did not react to the

decision |

|

|

|

RESISTANCE TO SCHOOL INTEGRATION

Within a year of the Brown

decision, more than 500 school districts in the nation had desegregated their classrooms. In

the cities of Baltimore, St. Louis, and Washington, D.C ., African-American and white students sat

side by side for the first time in history.

However, in areas where African Americans made up the

majority of the population, whites often resisted desegregation because they feared losing control of

the schools . In some places, the Ku Klux Klan reappeared and White Citizens Councils boycotted

businesses that supported desegregation. To hasten compliance, the Supreme Court handed down a second

Brown. ruling in 1955 that ordered district courts to implement school desegregation “with all

deliberate speed.” Neither Congress nor President Eisenhower moved to put teeth into the court

order. In Congress, more than 90 Southern members issued the “Southern Manifesto,” which

denounced the Brown decision and called on the states to resist it “by all lawful means.”

Although the president accepted the Courts ruling as law, he also confided privately to an aide,

“The fellow who tries to tell me that you can do these things by force is just plain nuts

.” Events in Little Rock, Arkansas, would soon force Eisenhower to act against this

belief. | |

|

|

|

67.

|

Why were white people afraid in

districts where black people made-up a majority of the citizens?

a. | Whites were afraid that they would

have to incorporate “black studies” into the curriculum | c. | Whites were afraid they would loose control of the

schools | b. | Whites were afraid blacks and whites would have to go to school

together | d. | Whites were afraid of the increased

costs of educating black students |

|

|

|

68.

|

A second Brown decision was

handed down by the Supreme Court in 1955. What did it say.

a. | The schools can take as much time as

they needed to desegregate | c. | The schools did not have to desegregate if they were planning on a challenge

to the 1954 Brown decision | b. | The schools must desegregate right away | d. | The schools must segregate right

away |

|

|

|

69.

|

In Congress, more than 90

Southern members issued the “Southern Manifesto,” What did it say?

a. | States should use any lawful means

to resist desegregation | c. | States should use

any means, even violence, to resist desegregation | b. | States should use any lawful means to resist

segregation | d. | States should use any means, even

violence, to resist segregation |

|

|

|

CRISIS IN LITTLE ROCK CRISIS IN LITTLE ROCK

In 1948, Arkansas had become the first Southern state to

admit African Americans to the state universities without being required by a court order. By the

1950s, some scout troops and labor unions in Arkansas had quietly ended their Jim Crow practices. In

Little Rock itself; citizens had elected two men to the school board who publicly backed

desegregation-and the school superintendent, Virgil Blossom, had been working on a plan for gradual

desegregation since 1953. However, state politics created an explosive situation . Caught in a tight

reelection race, Governor Orval Faubus jumped on the segregationist bandwagon . In September 1957, he

ordered the National Guard to turn away the nine African-American students who had volunteered to

integrate Little Rock’s Central High School as the first step in Blossom’s

| plan.

That afternoon, a federal judge ordered Faubus to let the students into school the next day. Eight

members of the “Little Rock Nine” received phone calls from ministers who volunteered to

escort the students to school for their safety. The family of the ninth student, Elizabeth Eckford,

did not have a phone . The next morning, she put on the carefully ironed white-and-black dress she

had made for her first day at an integrated school and set out alone . On the sidewalk outside

Central High, Eckford faced an abusive crowd of students and adults . Terrified, the 15-year-old

Eckford searched the mob for a friendly face. “I looked into the face of an old woman, and it

seemed a kind face,” she later told one interviewer. “But when I looked at her again, she

spat on me.” Trailed by the mob, Eckford managed to make it to a bus stop, where two friendly

whites stayed with her until the bus came. Eisenhower placed the Arkansas National Guard

under federal control and ordered a thousand paratroopers into Little Rock. Under the watchful eye of

these soldiers, the nine African American teenagers attended class. But even these soldiers could not

protect the students from troublemakers who confronted them on stairways, in the halls, and in the

cafeteria. Nor could the soldiers block interference by Faubus, who shut down Central High at the end

of the school year rather than let integration continue.

| | |

|

|

|

70.

|

Why did Governor Orval Faubus try to stop integration of Little

Rock Central High School?

a. | He was an old time

segregationist | c. | He did not try to

block integration at Central High School | b. | He thought integration would cost the city too much

money | d. | He was trying to be popular with the voters of

Arkansas |

|

|

|

71.

|

_____ was governor of _____

during the _____ high school incident in Little Rock.

a. | Orville Faubus - Alabama -

Central | c. | George Wallace -

Alabama - Northeast | b. | Orville Faubus - Arkansas - Central | d. | George Wallace - Mississippi -

Lincoln |

|

|

|

72.

|

Who did Governor Faubus use to

turn away the black students who were trying to enroll in Central High School.

a. | The Little Rock Police

force | c. | The Arkansas Highway

Patrol | b. | The Little Rock National Guard | d. | The Arkansas National Guard |

|

|

|

73.

|

What did President Eisenhower

do to force Central High School to accept the 9 black students?

a. | made Central High School a Federal

High School so it was no longer under the control of Arkansas | c. | placed the Arkansas National Guard under federal control

and ordered a thousand paratroopers into Little Rock | b. | Eisenhower did nothing because he was against integration

of the schools | d. | Eisenhower did nothing because he

was afraid |

|

|

|

74.

|

At the end of the school year,

what did Governor Faubus do to Central High School in Little Rock Arkansas?

a. | finally allowed the school to be

integrated | c. | made it a private

school | b. | turned the school into an all black high

school | d. | shut the high school rather than

integrate |

|

|

|

75.

|

In the United States the

schools are under the control of the states. What gave the U.S. government the right to force the

schools in Little Rock, Arkansas to integrate?

a. | the Brown v Board of Education

decision by the U.S. Supreme Court | c. | The U.S. government had no right to force the states to

integrate | b. | the Brown v Board of Education decision by the state

courts | d. | The Plessy v Ferguson decision by the Supreme Court of the

U.S. |

|

|

|

The Montgomery

Bus Boycott

The face-to-face confrontation at Central High School was not the only

showdown over segregation in the mid-1950s. Impatient with the slow pace of change in the courts,

African-American activists had begun taking direct action to win the rights promised to them by the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution .The Fourteenth Amendment promised

“equal protection of the law” (everyone in America should be treated equally. The

Fifteenth Amendment extended the right to vote to African American men by stating that race should

not be used to deny the right to vote. Among those on the frontline of change was Rosa

Parks. |

| | Long before December 1955, Rosa

Parks had protested segregation through everyday acts . She refused to use drinking fountains

labeled “Colored Only .” When possible, she shunned segregated elevators and climbed

stairs instead . Parks joined the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP in 1943 and became the

organization’s secretary. A turning point came for her in the summer of 1955, when she attended

a workshop at the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee . Highlander’s program was

designed to promote integration by giving the students the experience of interracial living .

Returning to Montgomery, Parks was even more determined to fight segregation . As it happened, her

act of protest against injustice on the buses inspired a whole community to join her

cause | | |

|

|

|

76.

|

What does the 14th Amendment

guarantee to every American?

a. | The right to

vote | c. | That the laws will be applied

equally to everyone | b. | The right to a happy life | d. | That everyone will get an equal

education |

|

|

|

77.

|

The 15th Amendment guarantees

that _____

a. | everyone living in the U.S. has the

right to vote | c. | African American

men and women shall have the right to vote. | b. | the right to vote will not be denied because of a persons

race | d. | the laws will be applied equally to black and white

people |

|

|

|

78.

|

Rosa Parks protested the Jim

Crow laws by .....

a. | refusing to use “colored

only” facilities. | c. | by picketing the

Montgomery bus company | b. | by picketing the Alabama state house | d. | by refusing to attend black

churches |

|

|

|

79.

|

From the reading it is clear

that Rosa Parks was interested in promoting

a. | “Black

Power” | c. | African American

businesses, such as a Montgomery bus company | b. | segregated facilities in

Alabama | d. | integration of the

races. |

|

|

|

BOYCOTTING

SEGREGATION

Among those on the frontline of change was Jo Ann Robinson. Four days after

the Brown decision in May 1954, Robinson wrote a letter to the mayor of Montgomery, Alabama, asking

that bus drivers no longer be allowed to force riders in the “colored” section to yield

their seats to whites. “More and more of our people are already arranging with neighbors and

friends for rides to keep from being insulted and humiliated by bus drivers,” Robinson warned .

The mayor refused.

On December 1,

1955, Rosa Parks, a seamstress and an NAACP officer, took a seat in the front row of the

“colored” section of a Montgomery bus. As |

| the bus filled up, the driver ordered Parks and three other African-American passengers

to empty the row they were occupying so that a white man could sit down without having to sit next to

any African Americans. “It certainly was time for someone to stand up,” recalled Parks

wryly. “So I refused to move.” As Parks stared out the window, the bus driver said,

“If you don’t stand up, I’m going to call the police and have you arrested .”

The soft spoken Parks replied, “You may do that.”

News of Parks’s arrest spread

rapidly. Jo Ann Robinson and NAACP leader E . D. Nixon quickly organized a boycott of the buses . The

leaders of the African-American community, including many ministers, formed the Montgomery

Improvement Association to organize the boycott. They elected the pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist

Church, 26-year-old Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., to lead the group. “Well, I’m not sure

I’m the best person for the position,” King confided to Nixon. “But if no one else

is going to serve, I’d be glad to try. | | |

|

|

|

80.

|

Jo Ann Robinson warned the

mayor of Montgomery, Alabama that black people were tired of being humiliated on the bus system and

were planning to take action. What was the mayor’s response?

a. | He suggested that they sit down and

talk | c. | He called out the National

Guard | b. | He told her that the Montgomery bus system would never be

integrated. | d. | He ignored

her. |

|

|

|

81.

|

What did Rosa Parks

do?

a. | She brought the issue of bus

segregation to the forefront | d. | She did all of these things | b. | She challenged Jim Crow

laws | e. | She did all of these things except challenge Jim Crow

laws | c. | She focused attention on the inequities of segregation in the

South. |

|

|

|

82.

|

What did the African American

community do in response to the arrest of Rosa Parks

a. | Called a general strike against all

Montgomery businesses | c. | Rioted and burned

many Montgomery busses | b. | Organized a boycott the bus system | d. | Lay in the streets and refused to allow any busses to

pass. |

|

|

|

83.

|

_____ was elected leader of the

Montgomery Improvement Association which was organized to lead a _____

a. | Martin Luther King - riots against

white owned businesses, including the but system | c. | Martin Luther King - boycott of the bus

system | b. | Jo Ann Robinson. - boycott of the bus system | d. | Rosa Parks - fight bus

segregation |

|

|

|

WALKING FOR JUSTICE

On the night of December 5,

1955, an estimated crowd of 5,000 people gathered to hear the young pastor speak. With passion and

eloquence. Dr. King made the following declaration.

There comes a time when people get

tired of being trampled over by the iron feet of oppression . . . . I want it to be known-that

we’re going to work with grim and bold determination-to gain justice on buses in this city .

And we are not wrong . . . . If we are wrong-the Supreme Court of this nation is wrong. If we are

wrong-God Almighty is wrong. . . . If we are wrong-justice is a lie.

The impact of

King’s speech-the rhythm of his words, the power of his rising and falling voice brought people

to their feet. A sense of mission filled the audience as King proclaimed, “If you will protest

courageously and yet with dignity, historians will have to pause and say, ‘There lived a great

people-a black people-who injected a new meaning and dignity into the veins of

civilization.”’ For 381 days, African Americans refused to ride the buses in

Montgomery. In most cases, they had to find other means of transportation by organizing car

pools or walking long distances . The boycotters remained nonviolent even after a bomb ripped apart

King’s home . (Fortunately, no one was injured.) Finally, in late 1956, the Supreme Court

outlawed bus | segregation in

response to a lawsuit filed by the boycotters . On December 21, King boarded a Montgomery bus and sat

in the front. “It was a great ride,” he declared.

| | |

|

|

|

84.

|

Martin Luther King proposed a

course of non-violence in the Montgomery bus boycott because he was not at all sure that a bus

boycott was the right thing to do.

|

|

|

85.

|

The Montgomery bus boycott

lasted just over

a. | a year | c. | a half year | b. | two years | d. | three years |

|

|

|

86.

|

The segregated busses of

Montgomery, Alabama were finally outlawed by

a. | the Montgomery City

Council | c. | the Supreme Court

of the U.S. | b. | the Montgomery bus company | d. | the governor of Alabama |

|

|

|

Dr. King and the SCLC

The Montgomery bus boycott proved to the world that

ordinary African Americans could unite and organize a successful protest movement. It also proved the

power of nonviolent resistance, the peaceful refusal to obey unjust laws. Despite threats to his life

and family, King urged his followers, “Let nobody pull you so low as to hate

them.” | | | |

|

|

|

87.

|

Martin Luther learned from the

Montgomery bus boycott that _____ could be used to win the war against segregation

a. | violent

aggression | c. | non-violent

submission to the law | b. | peaceful resistance to the law | d. | obeying the law |

|

|

|

88.

|

Dr. King thought that hating

your enemies was

a. | justified | c. | foolish | b. | necessary | d. | immoral |

|

|

|

CHANGING THE WORLD WITH SOUL FORCE

King called his brand of

nonviolent resistance “soul force.” He based his ideas on the teachings of several people

.

From Jesus, he learned to love one’s enemies.

From writer Henry David

Thoreau, he took the concept of civil disobedience-the refusal to obey an unjust law.

From labor

organizer A. Philip Randolph, he learned techniques for organizing massive demonstrations.

From Mohandas Gandhi, the leader who helped India throw off British rule, he

learned that one could powerfully resist oppression without resorting to violence

.

King summed up his

philosophy by saying to white racists, “We will not hate you, but we cannot . . . obey your

unjust laws . We will soon wear you down by our capacity to suffer. And in winning our freedom, we

will so appeal to your heart and conscience that we will win you in the process.”

Some

African Americans questioned King’s peaceful philosophy when, after the Brown decision,

anti-black violence swept parts of the Deep South. The violence, aimed at keeping African Americans

“in their place,” included the highly publicized 1955 murder of Emmett Till-a 14-year-old

who had allegedly flirted with a white woman. There were also shootings and beatings, some

fatal, of civil rights workers. Despite these vicious attacks, King steadfastly preached the power of

nonviolence.

| |

|

|

|

89.

|

From _____ Dr. King learned to

love your enemies.

a. | A. Philip

Randolph, | c. | Jesus | b. | Henry David Thoreau | d. | Gandhi |

|

|

|

90.

|

In 1955, after violent attacks

on several African Americans, some black people began to question Dr. King’s non-violent

methods. King also began to question his own methods.

|

|

|

91.

|

What was “Soul

Force?”

a. | The ability to force your enemies

with violence to agree with you. | c. | The use of non-violence to convince your enemies to

change | b. | The ability to force your enemies to give in, even though they do not agree

with you. | d. | The use of force to defeat your

enemies |

|

|

|

| FROM THE

GRASSROOTS UP

After the boycott ended, King joined with more than 100 ministers and civil rights

leaders in 1957 to found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) . The purpose of

the SCLC, as stated by King, was “to carry on nonviolent crusades against the evils of

second-class citizenship .” Using African-American churches as a base, the SCLC planned to

stage protests and demonstrations throughout the South.

Leaders of the SCLC hoped to build a

movement from the grassroots up and to win the support of ordinary African Americans of all ages.

King, president of the SCLC, used the | power of his

voice and ideas to fuel the movement’s momentum. The nuts and bolts of organizing the SCLC fell

to Ella Baker, a former NAACP activist and the granddaughter of a slave minister .

While with the

NAACP, Baker had served as national field secretary, traveling over 16,000 miles throughout the South

. From 1959 to 1961, Baker used her contacts to set up branches of the SCLC in 65 Southern cities .

In April 1960, Baker helped students at Shaw University, an African-American university in Raleigh,

North Carolina, to organize the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC, pronounced

“snick” for short. It had been six years since the Brown case, and many college

students viewed the pace of change as too slow. Although these students risked a great deal-losing

college scholarships, being expelled from college, being physically harmed-they were determined to

challenge the system . SNCC, which hoped to harness the energy of these student protesters, would

soon create one of the most important student activist movements in the nation’s

history. | | |

|

|

|

92.

|

The Southern Christian

Leadership Council (SCLC) was a _____ based organization.

a. | church | c. | civic | b. | student | d. | business |

|

|

|

93.

|

Who was the organizer of the

Southern Christian Leadership Council?

a. | Rosa

Parks | c. | Martin Luther

King | b. | Ella Baker | d. | Thurgood Marshall |

|

|

|

94.

|

Why was Student Nonviolent

Coordinating Committee, or SNCC organized?

a. | Students were demanding more

scholarships | c. | Students thought

the pace of integration was too slow | b. | Students did not want to integrate with white

students | d. | Students thought the Southern

Christian Leadership Conference was moving too fast and not paying attention to concerns of

students. |

|

|

|

The Movement

Spreads

Although SNCC

adopted King’s ideas in part, its members had ideas of their own. Many wanted a more

confrontational strategy and set out to reshape the civil rights movement.

In those days there

were stores called 5 and dimes. Many of these stores had lunch counters where shoppers could each

lunch. Originally KMart was a 5 and dime called Kresgies | | DEMONSTRATING FOR FREEDOM

The founders

of SNCC had models to build on . In 1942, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) had staged the first

sit-ins, in which African-American protesters sat down at segregated lunch counters in Chicago and

refused to leave until they were served . In February 1960, African-American students from North

Carolina’s Agricultural and Technical College staged a sit-in at a whites-only lunch counter at

a Woolworth’s store in Greensboro . This time, television crews brought coverage of the protest

into homes throughout the United States . Day after day, reporters captured the ugly face of

racism-scenes of whites beating, jeering at, and pouring food over students who refused to strike

back. The coverage sparked many other sit-ins across the South. Store managers called in the

police, raised the price of food, and removed counter seats. But the movement continued and spread to

the North. There students formed picket lines around national chain stores that maintained segregated

lunch counters in the South.

NO TURNING BACK

By late 1960, students had descended on and

desegregated Jim Crow lunch counters in some 48 cities in 11 states . They endured arrests, beatings,

suspension from college, and tear gas and fire hoses, but the army of nonviolent students refused to

back down . “My mother has always told me that I’m equal to other people,” said

Ezell Blair, Jr., one of the students who led the first sit-in 1960. For the rest of the 1960s, many

Americans persevered to prove Blair’s mother correct. | | |

|

|

|

95.

|

A Jim Crow lunch counter is one

where

a. | black and whites sat in separate

sections of the same counter | c. | food was served that only white people liked | b. | black people were not allowed to sit and eat with white

people | d. | food was served that only black people

liked |

|

|

|

96.

|

SNCC was comprised mostly of

a. | members of

CORE | c. | young civil rights

activists | b. | older veterans of the civil rights movement | d. | members of SCLC |

|

|

|

97.

|

Why didn’t the sit-in

demonstrators fight back at the people who jeered and humiliated them?

a. | They were following the principles

taught by Marcus Garvey | c. | They were afraid

of the anti-sit in demonstrators | b. | They were following the lessons of taught by Martin Luther

King | d. | They were afraid of going to Southern

jails |

|

|

|

98.

|

CORE is an old civil rights

organization that has been working for racial equality for many years. CORE stands for

a. | Colored Organization of Racial

Enthusiasts | c. | Congress Of Racial

Entigration | b. | Congress of Old Racial Energy | d. | Congress of Racial Equality |

|

|

|

99.

|

Demonstrations organized by the

SCLC were effective but SNCC demonstrations were not.

|

|

|

100.

|

In the 1960’s most

Americans outside the South were unaware of the civil rights movement.

|

|

|

African Americans Seek Greater

Equality

By 1965, the leading

civil rights groups-while still sharing the goals of racial equality and greater opportunity-began to

drift apart. New leaders emerged as the civil rights movement turned its attention to the North,

where African Americans faced not legal racism but deeply entrenched and oppressive racial prejudice

nonetheless.

NORTHERN SEGREGATION The problem in the North was de facto segregation-

segregation that exists by practice and custom . De facto segregation can be harder to fight than de

jure segregation (segregation by law), because eliminating it requires the transformation of racist

attitudes rather than the repeal of Jim Crow laws. Activists in the mid-1960s would find it much more

difficult to convince whites to share economic and social power with African Americans than to

convince them to share lunch counters and bus seats.

De facto segregation intensified after African Americans

migrated to Northern cities after World War 11. This began a “white flight,” in which

great numbers of white city dwellers moved to the suburbs . By the mid-1960s, most urban African

Americans found themselves trapped in decaying slums, paying rent to landlords who often refused to

comply with local housing and health ordinances . The schools provided for African-American children

deteriorated along with their neighborhoods . Unemployment rates among African Americans were more

than twice as high as those among whites . The widely publicized gains in voting rights and

desegregation of public accommodations made many urban African Americans impatient for discrimination

in other areas to end. In addition, they were angry at the sometimes brutal treatment they received

from the mostly white police force that patrolled their communities

.

| |

|

|

|

101.

|

By 1965 the civil rights

leaders turn their attention _____ where another kind of racism existed.

a. | to the

West | c. | to the

farmlands | b. | to the North | d. | outside of America |

|

|

|

102.

|

Segregation that is in place by

custom and tradition, but not necessarily by law is called

a. | local

segregation | c. | de facto

segregation | b. | national segregation | d. | state segregation |

|

|

|

103.

|

When black people moved into

Northern cities after World War II, what did white residents do?

a. | Fought integration by going to

court | c. | Joined the

KKK | b. | Refused to sell their houses to blacks | d. | Fled to the Suburbs |

|

|

|

104.

|

In the 50’s and early