Multiple Choice

Identify the

choice that best completes the statement or answers the question.

|

|

|

Section 1 The Nominating Process

· The nominating process is critically important to democratic

government.

· Five major nominating methods are used in American politics.

· The most widely used nominating method today is the direct

primary

Objectives

1. Explain why the nominating process is a critical first step in the election process.

2. Describe self-announcement, the caucus, and the convention as nominating methods.

3. Discuss the direct primary as the principal nominating method used in the United

States today.

4. Understand why some candidates use the petition as a nominating

device.

Why It Matters

The nominating process, however it is conducted, is a critically important

step in electoral politics for a number of reasons. Not the least of these: It is from among those

who are nominated that the voters pick the men and women who will serve in public office in this

country.

Political Dictionary

nomination

The process of candidate

selection in an electoral system

general election

The regularly scheduled election

at which voters make a final selection of officeholders.

caucus

As a nominating

device, a group of like-minded people who meet to select the candidates they will support in an

upcoming election.

direct primary

An election held within a party to pick that

party's candidates for the general election.

closed primary

A party nominating

election in which only declared party members can vote.

open primary

A

party-nominating election in which any qualified voter can take part.

blanket primary

A voting process in which voters receive a long ballot containing the names of all

contenders, regardless of party, and can vote however they choose.

runoff primary

A

primary in which the top two vote-getters in the first direct primary face one

another.

nonpartisan election

Elections in which candidates are not identified by

party labels.

|

|

|

1.

|

Why is the nominating process

important?

a. | It is good for

business | c. | It is important to

the democratic process | b. | It does a job that the people are too lazy to

do | d. | It guarantees that smart people will always be

elected |

|

|

|

A

Critical First Step

The nominating process is the process of candidate selection. Nomination—the naming of

those who will seek office—is a critically important step in the election process.

The

nominating process also has a very real impact on the right to vote. In most elections in this

country, voters can choose between only two candidates for each office on the ballot. They can vote

for the Republican or they can vote for the Democratic candidate.1 This is another way of

saying that we have a two-party system in the United States. It is also another way to say that the

nominating stage is a critically important part of the electoral process. Those who win nominations

place real, very practical limits on the choices that voters can make in an election.

In some

constituencies one party is so strong they are the only party that has a chance of winning.. Once the

dominant party has made its nomination, the general election is little more than a formality.

Dictatorial regimes point

up the importance of the nominating process. Many of them hold general

elections—regularly scheduled elections at which voters make the final selection of

officeholders—much as democracies do. But typically, the ballots used in those elections list

only one candidate for each office—the candidate of the ruling clique; and those candidates

regularly win with majorities approaching 100 percent.

There are five ways in which

nominations are made in the United States. They include (1) self-announcement, (2) caucus, (3)

convention, (4) direct primary, and (5) petition.

|

|

|

2.

|

How does the nomination process

impact the right to vote?

a. | Only one candidate can be

elected | c. | Only Republicans

and Democrats can vote | b. | By nominating only two candidates the choice of candidates is

limited | d. | Union workers are not allowed to vote for

Republicans |

|

|

|

3.

|

When is the general election

only a formality?

a. | when one party strongly dominates

| c. | when no party strongly

dominates | b. | when candidates are weak | d. | when candidates do not belong to any

party |

|

|

|

4.

|

If an election has only one

candidate who receives nearly 100% of the vote we call the country a

a. | democracy | c. | direct democracy | b. | republic | d. | dictatorship |

|

|

|

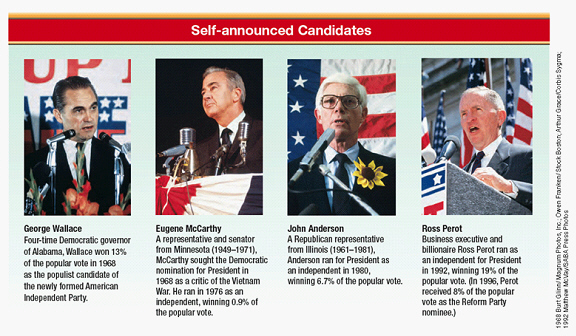

Self-Announcement

Self-announcement is the oldest form of the nominating process in American

politics. First used in colonial times, it is still often found at the small-town and rural levels in

many parts of the country

The method is quite simple. A person who

wants to run for office simply announces that fact. Modesty or local custom may dictate that someone

else make the candidate’s announcement, but, still, the process amounts to the same thing. The method is quite simple. A person who

wants to run for office simply announces that fact. Modesty or local custom may dictate that someone

else make the candidate’s announcement, but, still, the process amounts to the same thing.

Self-announcement is sometimes

used by someone who failed to win a regular party nomination or by someone unhappy with the

party’s choice. Note that whenever a write-in candidate appears in an election, the

self-announcement process has been used. In recent history, four prominent presidential contenders

have made use of the process: George Wallace, who declared himself to be the American Independent

Party’s nominee in 1968; and independent candidates Eugene McCarthy in 1976; John Anderson in

1980; and Ross Perot in 1992. And all of the 135 candidates who sought to replace Governor Gray

Davis of California in that State’s recall election in 2003—including the winner, Arnold

Schwarzenegger—were self-starters.

|

|

|

5.

|

Why do some people nominate

themselves for office?

a. | they want to help the regular party

candidate | c. | They do not have

enough money to run as part of a party | b. | they don’t like the regular party

candidates | d. | Their religion keeps them from

joining a party |

|

|

|

The

Caucus

As a nominating device, a caucus is a group of like-minded people

who meet to select the candidates they will support in an upcoming election. The first caucus

nominations were made during the later colonial period, probably in Boston in the 1720s.2 John Adams described the

caucus this way in 1763

Originally

the caucus was a private meeting consisting of a few influential figures in the community. As

political parties appeared in the late 1700s, they soon took over the device and began to broaden the

membership of the caucus

The

coming of independence brought the need to nominate candidates for State offices: governor,

lieutenant governor, and others above the local level. The legislative caucus—a meeting of a

party’s members in the State legislature—took on the job. At the national level, both the

Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans in Congress were, by 1800, choosing their presidential and

vice-presidential candidates through the congressional caucus.

The legislative and congressional caucuses were quite

practical in their day. Transportation and communication were difficult at best. Since legislators

already gathered regularly in a central place, it made sense for them to take on the nominating

responsibility. The spread of democracy, especially in the newer States on the frontier, spurred

opposition to caucuses, however. More and more, people condemned them for their closed,

unrepresentative character.

Criticism of the caucus reached its peak in the early 1820s. The

supporters of three of the leading contenders for the presidency in 1824—Andrew Jackson, Henry

Clay, and John Quincy Adams—boycotted the Democratic-Republicans’ congressional caucus

that year. In fact, Jackson and his supporters made “King Caucus” a leading campaign

issue. The other major aspirant, William H. Crawford of Georgia, became the caucus nominee at a

meeting attended by fewer than one third of the Democratic-Republican Party’s members in

Congress.

Crawford ran a poor third in the electoral college balloting in 1824, and the reign of

King Caucus at the national level was ended. With its death in presidential politics, the caucus

system soon withered at the State and local levels, as well.

The caucus is still used to make

local nominations in some places, especially in New England. There, a caucus is open to all members

of a party, and it only faintly resembles the original closed and private

process.

|

|

|

6.

|

What is a

caucus?

a. | A group of people with similar ideas

get together to make decisions or choose candidates | c. | A way to raise money for candidates | b. | An agency hired by a campaign to win an

election | d. | The presidents

family |

|

|

|

The

Convention

As the caucus method collapsed, the convention system took its place. The

first national convention to nominate a presidential candidate was held by a minor party, the

Anti-Masons, in Baltimore in 1831. The newly formed National Republican (soon to become Whig) Party

also held a convention later that same year. The Democrats picked up the practice in 1832. All

major-party presidential nominees have been chosen by conventions ever since. By the 1840s,

conventions had become the principal means for making nominations at every level in American

politics.

On paper, the convention process seems perfectly suited to representative government. A

party’s members meet in a local caucus to pick candidates for local offices and, at the same

time, to select delegates to represent them at a county convention.3

At the county

convention, the delegates nominate candidates for county offices and select delegates to the next

rung on the convention ladder, usually the State convention. There, the delegates from the county

conventions pick the party’s nominees for governor and other State-wide offices. State

conventions also send delegates to the party’s national convention, where the party selects its

presidential and vice-presidential candidates.

In theory, the will of the party’s rank and

file membership is passed up through each of its representative levels. Practice soon pointed up the

weaknesses of the theory, however, as party bosses found ways to manipulate the process. By playing

with the selection of delegates, usually at the local levels, they soon dominated the entire system.

As a result, the caliber of most conventions declined at all levels, especially during the late

1800s. How low some of them fell can be seen in this description of a Cook County, Illinois,

convention in 1896:

Many people

had hailed the change from caucus to convention as a major change for the better in American

politics. The abuses of the new device soon dashed their hopes. By the 1870s, the convention system

was itself under attack as a major source of evil in American politics. By the 1910s, the direct

primary had replaced the convention in most States as the principal nominating method in American

politics.

Conventions still play a

major role in the nominating process in some States—notably, Connecticut, Michigan, South

Dakota, Utah, and Virginia. And, as you will see, no adequate substitute for the device has yet been

found at the presidential level.

|

|

|

7.

|

What is one way that groups try

to control conventions?

a. | by controlling who is selected as

delegates to the convention | c. | by imposing a dress code | b. | by keeping the convention

secret | d. | by opening it up to everyone who wants to

attend |

|

|

|

8.

|

What process has replaced the

convention as the main nominating process in America?

a. | the direct

primary | c. | the indirect

primary | b. | the general election | d. | the town hall meeting |

|

|

|

The

Direct Primary

A direct

primary is an intra-party election. It is held within a party to pick that party’s

candidates for the general election. Wisconsin adopted the first State-wide direct primary law in

1903; several other States soon followed its lead. Every State now makes at least some provision for

its use.

In most States, State law requires that the major parties use the primary to choose their

candidates for the United States Senate and House of Representatives, for the governorship and all

other State offices, and for most local offices as well. In a few States, however, different

combinations of convention and primary are used to pick candidates for the top offices.

In

Michigan, for example, the major parties choose their candidates for the U.S. Senate and House, the

governorship, and the State legislature in primaries. Nominees for lieutenant governor, secretary of

state, and attorney general are picked by conventions.4

Although the primaries

are party-nominating elections, they are closely regulated by law in most States. The State usually

sets the dates on which primaries are held, and it regularly conducts them, too. The State, not the

parties, provides polling places and election officials, registration lists and ballots, and

otherwise polices the process.

Two basic forms of the direct primary are in use today: (1) the

closed primary and (2) the open primary. The major difference between the two lies in the answer to

this question: Who can vote in a party’s primary—only qualified voters who are party

members, or any qualified

voter?

|

|

|

9.

|

What is a direct

primary?

a. | an inter-party

election | c. | a general

election | b. | an intra-party election | d. | an independent party election |

|

|

|

The Closed Primary

Today, 27 States provide for the closed primary—a

party’s nominating election in which only declared party members can vote. The party’s

primary is closed to all but those party members.5

In most of the closed

primary States, party membership is established by registration; see page 154. When voters

appear at their polling places on primary election day, their names are checked against the poll

books and each voter is handed the primary ballot of the party in which he or she is registered. The

voter can mark only that

party’s ballot; he or she can vote only in that party’s primary.

In come of the

closed primary States, however, a voter can change his or her party registration on election day. in

those States, then, the primary is noan as completely “closed” as it is

elsewhere.

|

|

|

10.

|

What is a closed

primary?

a. | only voters who belong to the

opposite party may vote | c. | only voters who

belong to the party may vote | b. | a primary open for a specific period of

time. | d. | anyone can

vote |

|

|

|

The Open Primary

The open

primary is a party’s nominating election in which any qualified voter can cast a ballot. Although it

is the form in which the direct primary first appeared, it is now found in only 26 States.

When voters go to the polls in some open primary States, they are handed a ballot of each party

holding a primary. Usually, they receive two ballots, those of the Republican and the Democratic

parties. Then, in the privacy of the voting booth, each voter marks the ballot of the party in whose

primary he or she chooses to vote. In other open primary States, a voter must ask for the ballot of

the party in whose primary he or she wants to vote. That is, each voter must make a public

choice of party in order to vote in the primary.

Through 2000, three States used a different

version of the open primary—the blanket primary, sometimes

called the “wide-open primary.” Washington adopted the first blanket primary law in 1935.

Alaska followed suit in 1970, and California did so in 1996. In a blanket primary, every voter

received the same ballot—a long one that listed every candidate, regardless of party,

for every nomination to be made at the primary. Voters could participate however they chose. They

could confine themselves to one party’s primary; or they could switch back and forth between

the parties primaries, voting to nominate a Democrat for one office, a Republican for another, and so

on down the ballot.

The Supreme Court found California’s version of the blanket primary

unconstitutional in 2000, however. In California Democratic Party v. Jones, the High

Court held that process violated the 1st and 14th amendments’ guarantees of the right of

association. It ruled that a State cannot force a political party to associate with

outsiders—that is, with members of other parties or with independents—when it picks its

candidates for public office.

For 2002, California responded to the Court’s decision by

returning to the closed primary; and Alaska held a typical open primary. Washington did hold a

blanket primary in 2002, but it finally bowed to the High Court’s decision and, like Alaska, it

held an open primary in 2004.

Louisiana has yet another form of the open primary, which was not

affected by the Court’s decision in Jones. Its unique “open-election law”

provides for what amounts to a combination primary and election. The names of all the people who seek

nominations are listed by office on a single primary ballot, regardless of party. A contender who

wins more than 50 percent of the primary votes wins the office. In these cases, the primary

becomes the election. In contests where there is no majority winner, the two top vote-getters, again

regardless of party, face off in the general election.

|

|

|

11.

|

What is an open

primary?

a. | a primary in which voters from any

party may vote | c. | a primary open for

a specific period of time | b. | a primary in which only party members can

vote | d. | a primary in which only independent voters may

vote |

|

|

|

12.

|

What is a blanket

primary?

a. | a primary that covers the general

and primary elections | c. | a voter gets a

ballot with the names of candidates from all parties and votes for any that he

chooses | b. | a primary that is secret (covered). | d. | a voter gets a ballot with the names of candidates from one party and votes

for any that he chooses |

|

|

|

The Runoff Primary

In most States, candidates need to win only a plurality of the votes cast in

the primary to win their party’s nomination.7 (Remember, a

plurality is the greatest

number of votes won by any candidate, whether a majority or not.) In 11 States,8 however, an absolute

majority is needed to carry a primary. If no one wins a majority in a race, a runoff primary is held a few

weeks later. In that runoff, the two top vote-getters in the first party primary face one another for

the party’s nomination, and the winner of that vote becomes the nominee.

|

|

|

13.

|

If no candidate receives a

majority of votes, what kind of election do they have to decide who wins?

a. | closed primary

election | c. | runoff

election | b. | open primary election | d. | non partisan primary |

|

|

|

The Nonpartisan Primary

In most States all or nearly all of the elected school and municipal offices

are filled in nonpartisan

elections. These are elections in which candidates are not identified by party labels. About half

of all State judges are chosen on nonpartisan ballots, as well. The nomination of candidates for

these offices takes place on a nonpartisan basis, too, often in nonpartisan primaries.

Typically,

a contender who wins a clear majority in a nonpartisan primary then runs unopposed in the general

election, subject only to write-in opposition. In many States, however, a candidate who wins a

majority in the primary is declared elected at that point. If there is no majority winner, the names

of the two top contenders are placed on the general election ballot.

The primary first appeared

as a partisan nominating device. Many have long argued that it is not well suited for use in

nonpartisan elections. Instead, they favor the petition method, which you will consider later in this

section.

|

|

|

14.

|

In Nonpartisan

elections

a. | there are no election

rules | c. | candidates must declare their party

affiliation | b. | there are too many election rules | d. | candidates are not allowed to run as party

members |

|

|

|

Evaluation of the Primary

The direct primary, whether open or closed, is an intraparty nominating election. It came to American

politics as a reform of the boss-dominated convention system. It was intended to take the nominating

function away from the party organization and put it in the hands of the party’s membership.

The basic facts about the primary have never been very well understood by most voters, however.

So, in closed primary States, many voters resent having to declare their party preference. And, in

both open and closed primary States, many are upset because they cannot express their support for

candidates in more than one party. Many are also annoyed by the “bed-sheet ballots” they

regularly see in primary elections—not realizing that the use of the direct primary almost

automatically means a long ballot. And some are concerned because the primary (and, in particular,

its closed form) tends to exclude independents from the nominating process.

These factors,

combined with a lack of appreciation of the importance of primaries, result in this unfortunate fact:

Nearly everywhere, voter turnout in primary elections is usually less than half what it is in general

elections.

Primary campaigns can be quite costly. The fact that the successful contenders must

then wage—and finance—a general election campaign adds to the money problems that bedevil

American politics. Unfortunately, the financial facts of political life in the United States mean

that some well-qualified people do not seek public office simply because they cannot muster the

necessary funds.

The nominating process, whatever its form, can also have a very divisive effect

on a party. Remember, the process takes place within the party—so, when there is a

contest for a nomination, that is where the contest occurs. A bitter fight in the primaries can so

wound and divide a party that it cannot recover in time to present a united front for the general

election. Many a primary fight has cost a party an election.

Finally, because many voters are not

very well informed, the primary places a premium on name familiarity. That is, it often gives an edge

to a contender who has a well-known name or a name that sounds like that of some well-known person.

But, notice, name familiarity in and of itself has little or nothing to do with a candidate’s

qualifications for office.

Obviously, the primary is not without its problems, nor is any other

nominating device. Still, the primary does give a party’s members the opportunity to

participate at the very core of the political process.

|

|

|

15.

|

Why did people feel it was

necessary to have primary elections to choose candidates?

a. | to make the candidate selection

process more democratic | c. | to allow party

bosses to have more control over the candidate selection process | b. | to speed up the candidate selection

process | d. | to elect more intelligent people to

offices |

|

|

|

The Presidential Primary

The presidential primary developed as an offshoot of the direct primary. It is

not a nominating device, however. Rather, the presidential primary is an election that is held as one

part of the process by which presidential candidates are chosen.

The presidential primary is a

very complex process. It is one or both of two things, depending on the State involved. It is a

process in which a party’s voters elect some or all of a State party organization’s

delegates to that party’s national convention; and/or it is a preference election in which

voters can choose (vote their preference) among various contenders for a party’s presidential

nomination. Much of what happens in presidential politics in the early months of every fourth year

centers on this very complicated process. (See Chapter 13 for an extended discussion of the

presidential primary.)

|

|

|

16.

|

What is the purpose of the

Presidential Primary?

a. | help the president to pick a vice

president | c. | help the president

to pick his cabinet | b. | elect candidate supporters to go to the party

conventions | d. | to go around (circumvent) the

Electoral College |

|

|

|

Petition

One other nominating method is used fairly widely at the local level in

American politics today—nomination by petition. Where this process is used, candidates for

public office are nominated by means of petitions signed by a certain required number of qualified

voters in the election district

Nomination by petition is found most widely at the local level,

chiefly for nonpartisan school posts and municipal offices in medium-sized and smaller communities.

It is also the process usually required by State law for nominating minor party and independent

candidates. (Remember, the States often purposely make the process of getting on the ballot difficult

for those candidates.)

The details of the petition process vary widely from State to State, and

even from one city to the next. Usually, however, the higher the office and/or the larger the

constituency represented by the office, the greater the number of signatures needed for

nomination.

|

|

|

17.

|

In some local elections it is

possible to get the nomination by getting signatures on a petition

|

Multiple Response

Identify one

or more choices that best complete the statement or answer the question.

|

|

|

The

Caucus

As a nominating device, a caucus is a group of like-minded people

who meet to select the candidates they will support in an upcoming election. The first caucus

nominations were made during the later colonial period, probably in Boston in the 1720s.2 John Adams described the

caucus this way in 1763

Originally

the caucus was a private meeting consisting of a few influential figures in the community. As

political parties appeared in the late 1700s, they soon took over the device and began to broaden the

membership of the caucus

The

coming of independence brought the need to nominate candidates for State offices: governor,

lieutenant governor, and others above the local level. The legislative caucus—a meeting of a

party’s members in the State legislature—took on the job. At the national level, both the

Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans in Congress were, by 1800, choosing their presidential and

vice-presidential candidates through the congressional caucus.

The legislative and congressional caucuses were quite

practical in their day. Transportation and communication were difficult at best. Since legislators

already gathered regularly in a central place, it made sense for them to take on the nominating

responsibility. The spread of democracy, especially in the newer States on the frontier, spurred

opposition to caucuses, however. More and more, people condemned them for their closed,

unrepresentative character.

Criticism of the caucus reached its peak in the early 1820s. The

supporters of three of the leading contenders for the presidency in 1824—Andrew Jackson, Henry

Clay, and John Quincy Adams—boycotted the Democratic-Republicans’ congressional caucus

that year. In fact, Jackson and his supporters made “King Caucus” a leading campaign

issue. The other major aspirant, William H. Crawford of Georgia, became the caucus nominee at a

meeting attended by fewer than one third of the Democratic-Republican Party’s members in

Congress.

Crawford ran a poor third in the electoral college balloting in 1824, and the reign of

King Caucus at the national level was ended. With its death in presidential politics, the caucus

system soon withered at the State and local levels, as well.

The caucus is still used to make

local nominations in some places, especially in New England. There, a caucus is open to all members

of a party, and it only faintly resembles the original closed and private

process.

|

|

|

18.

|

What are some of the problems

with caucuses? (pick 2)

|

|

|

The

Direct Primary

A direct

primary is an intra-party election. It is held within a party to pick that party’s

candidates for the general election. Wisconsin adopted the first State-wide direct primary law in

1903; several other States soon followed its lead. Every State now makes at least some provision for

its use.

In most States, State law requires that the major parties use the primary to choose their

candidates for the United States Senate and House of Representatives, for the governorship and all

other State offices, and for most local offices as well. In a few States, however, different

combinations of convention and primary are used to pick candidates for the top offices.

In

Michigan, for example, the major parties choose their candidates for the U.S. Senate and House, the

governorship, and the State legislature in primaries. Nominees for lieutenant governor, secretary of

state, and attorney general are picked by conventions.4

Although the primaries

are party-nominating elections, they are closely regulated by law in most States. The State usually

sets the dates on which primaries are held, and it regularly conducts them, too. The State, not the

parties, provides polling places and election officials, registration lists and ballots, and

otherwise polices the process.

Two basic forms of the direct primary are in use today: (1) the

closed primary and (2) the open primary. The major difference between the two lies in the answer to

this question: Who can vote in a party’s primary—only qualified voters who are party

members, or any qualified

voter?

|

|

|

19.

|

What are two types of direct

primaries? (pick 2)

|

|

|

Closed vs. Open Primary

The two basic forms of the primary have caused arguments for decades. Those

who favor the closed primary regularly make three arguments in support of it:

1. It prevents one

party from “raiding” the other’s primary in the hope of nominating weaker

candidates in the other party.

2. It helps make candidates more responsive to the party, its

platform, and its members.

3. It helps make voters more thoughtful, because they must choose

between the parties in order to vote in the primaries.

The critics of the closed primary contend

that:

1. It compromises the secrecy of the ballot, because it forces voters to make their party

preferences known in public, and

2. It tends to exclude independent voters from the nomination

process.6

Advocates of

the open primary believe that their system of nominating addresses both of these criticisms. In many

open primaries, (1) voters are not forced to make their party preferences known in public, and (2)

the tendency to exclude independent voters is eliminated. The opponents of the open primary insist

that it (1) permits primary “raiding” and (2) undercuts the concepts of party loyalty and

party responsibility.

|

|

|

20.

|

What are three arguments in

favor of closed primaries? (pick 3)

|

|

|

21.

|

What are two arguments against

closed primaries? (pick 2)

|

Matching

|

|

|

a. | nomination | f. | open primary | b. | general election | g. | blanket primary | c. | caucus | h. | runoff

primary | d. | direct primary | i. | nonpartisan election | e. | closed

primary |

|

|

|

22.

|

An intra-party election to

choose candidates to run for offices

|

|

|

23.

|

An election to pick candidates

to run that any voter can vote in

|

|

|

24.

|

An election where the

candidates do not run as members of a political party

|

|

|

25.

|

Picking a

candidate

|

|

|

26.

|

An election in which voters

have to pick between the top two candidates who got the most votes

|

|

|

27.

|

An election to pick candidates

to run that only party members can vote in

|

|

|

28.

|

The election that places a

candidate in the office he is running for

|

|

|

29.

|

An election in which voters

can see all candidates and vote for any of them

|

|

|

30.

|

People who come together in

person to choose a candidate

|